import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import pandas_datareader as pdr

import yfinance as yfMcKinney Chapter 11 - Time Series

FINA 6333 for Spring 2024

1 Introduction

Chapter 11 of Wes McKinney’s Python for Data Analysis discusses time series and panel data, which is where pandas shines. We will use these time series and panel tools every day for the rest of the course.

We will focus on:

- Slicing a data frame or series by date or date range

- Using

.shift()to create leads and lags of variables - Using

.resample()to change the frequency of variables - Using

.rolling()to aggregate data over rolling windows

Note: Indented block quotes are from McKinney unless otherwise indicated. The section numbers here differ from McKinney because we will only discuss some topics.

%precision 4

pd.options.display.float_format = '{:.4f}'.format

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'McKinney provides an excellent introduction to the concept of time series and panel data:

Time series data is an important form of structured data in many different fields, such as finance, economics, ecology, neuroscience, and physics. Anything that is observed or measured at many points in time forms a time series. Many time series are fixed frequency, which is to say that data points occur at regular intervals according to some rule, such as every 15 seconds, every 5 minutes, or once per month. Time series can also be irregular without a fixed unit of time or offset between units. How you mark and refer to time series data depends on the application, and you may have one of the following: - Timestamps, specific instants in time - Fixed periods, such as the month January 2007 or the full year 2010 - Intervals of time, indicated by a start and end timestamp. Periods can be thought of as special cases of intervals - Experiment or elapsed time; each timestamp is a measure of time relative to a particular start time (e.g., the diameter of a cookie baking each second since being placed in the oven)

In this chapter, I am mainly concerned with time series in the first three categories, though many of the techniques can be applied to experimental time series where the index may be an integer or floating-point number indicating elapsed time from the start of the experiment. The simplest and most widely used kind of time series are those indexed by timestamp. 323

pandas provides many built-in time series tools and data algorithms. You can effi‐ ciently work with very large time series and easily slice and dice, aggregate, and resample irregular- and fixed-frequency time series. Some of these tools are especially useful for financial and economics applications, but you could certainly use them to analyze server log data, too.

2 Time Series Basics

Let us create a time series to play with.

from datetime import datetime

dates = [

datetime(2011, 1, 2),

datetime(2011, 1, 5),

datetime(2011, 1, 7),

datetime(2011, 1, 8),

datetime(2011, 1, 10),

datetime(2011, 1, 12)

]

np.random.seed(42)

ts = pd.Series(np.random.randn(6), index=dates)

ts2011-01-02 0.4967

2011-01-05 -0.1383

2011-01-07 0.6477

2011-01-08 1.5230

2011-01-10 -0.2342

2011-01-12 -0.2341

dtype: float64Note that pandas converts the datetime objects to a pandas DatetimeIndex object and a single index value is a Timestamp object.

ts.indexDatetimeIndex(['2011-01-02', '2011-01-05', '2011-01-07', '2011-01-08',

'2011-01-10', '2011-01-12'],

dtype='datetime64[ns]', freq=None)ts.index[0]Timestamp('2011-01-02 00:00:00')Recall that arithmetic operations between pandas objects automatically align on indexes.

ts2011-01-02 0.4967

2011-01-05 -0.1383

2011-01-07 0.6477

2011-01-08 1.5230

2011-01-10 -0.2342

2011-01-12 -0.2341

dtype: float64ts.iloc[::2]2011-01-02 0.4967

2011-01-07 0.6477

2011-01-10 -0.2342

dtype: float64ts + ts.iloc[::2]2011-01-02 0.9934

2011-01-05 NaN

2011-01-07 1.2954

2011-01-08 NaN

2011-01-10 -0.4683

2011-01-12 NaN

dtype: float642.1 Indexing, Selection, Subsetting

pandas uses U.S.-style date strings (e.g., “M/D/Y”) or unambiguous date strings (e.g., “YYYY-MM-DD”) to select data.

ts['1/10/2011'] # M/D/YYYY-0.2342ts['2011-01-10'] # YYYY-MM-DD-0.2342ts['20110110'] # YYYYMMDD-0.2342ts['10-Jan-2011'] # D-Mon-YYYY-0.2342ts['Jan-10-2011'] # Mon-D-YYYY-0.2342But pandas does not use U.K.-style dates.

# # KeyError: '10/1/2011'

# ts['10/1/2011'] # D/M/YYYYHere is a longer time series we can use to learn about longer slices.

np.random.seed(42)

longer_ts = pd.Series(

data=np.random.randn(1000),

index=pd.date_range('1/1/2000', periods=1000)

)

longer_ts2000-01-01 0.4967

2000-01-02 -0.1383

2000-01-03 0.6477

2000-01-04 1.5230

2000-01-05 -0.2342

...

2002-09-22 -0.2811

2002-09-23 1.7977

2002-09-24 0.6408

2002-09-25 -0.5712

2002-09-26 0.5726

Freq: D, Length: 1000, dtype: float64We can pass a year-month to slice all of the observations in May of 2001.

longer_ts['2001-05']2001-05-01 -0.6466

2001-05-02 -1.0815

2001-05-03 1.6871

2001-05-04 0.8816

2001-05-05 -0.0080

2001-05-06 1.4799

2001-05-07 0.0774

2001-05-08 -0.8613

2001-05-09 1.5231

2001-05-10 0.5389

2001-05-11 -1.0372

2001-05-12 -0.1903

2001-05-13 -0.8756

2001-05-14 -1.3828

2001-05-15 0.9262

2001-05-16 1.9094

2001-05-17 -1.3986

2001-05-18 0.5630

2001-05-19 -0.6506

2001-05-20 -0.4871

2001-05-21 -0.5924

2001-05-22 -0.8640

2001-05-23 0.0485

2001-05-24 -0.8310

2001-05-25 0.2705

2001-05-26 -0.0502

2001-05-27 -0.2389

2001-05-28 -0.9076

2001-05-29 -0.5768

2001-05-30 0.7554

2001-05-31 0.5009

Freq: D, dtype: float64We can also pass a year to slice all observations in 2001.

longer_ts['2001']2001-01-01 0.2241

2001-01-02 0.0126

2001-01-03 0.0977

2001-01-04 -0.7730

2001-01-05 0.0245

...

2001-12-27 0.0184

2001-12-28 0.3476

2001-12-29 -0.5398

2001-12-30 -0.7783

2001-12-31 0.1958

Freq: D, Length: 365, dtype: float64If we sort our data chronologically, we can also slice with a range of date strings.

ts['1/6/2011':'1/10/2011']2011-01-07 0.6477

2011-01-08 1.5230

2011-01-10 -0.2342

dtype: float64However, we cannot date slice if our data are not sorted chronologically.

ts2 = ts.sort_values()

ts22011-01-10 -0.2342

2011-01-12 -0.2341

2011-01-05 -0.1383

2011-01-02 0.4967

2011-01-07 0.6477

2011-01-08 1.5230

dtype: float64For example, the following date slice fails because ts2 is not sorted chronologically.

# # KeyError: 'Value based partial slicing on non-monotonic DatetimeIndexes with non-existing keys is not allowed.'

# ts2['1/6/2011':'1/11/2011']We can use the .sort_index() method first to allow date slices.

ts2.sort_index()['1/6/2011':'1/11/2011']2011-01-07 0.6477

2011-01-08 1.5230

2011-01-10 -0.2342

dtype: float64To be clear, a range of date strings is inclusive on both ends.

longer_ts['1/6/2001':'1/11/2001']2001-01-06 0.4980

2001-01-07 1.4511

2001-01-08 0.9593

2001-01-09 2.1532

2001-01-10 -0.7673

2001-01-11 0.8723

Freq: D, dtype: float64Recall, if we modify a slice, we modify the original series or dataframe.

Remember that slicing in this manner produces views on the source time series like slicing NumPy arrays. This means that no data is copied and modifications on the slice will be reflected in the original data.

ts3 = ts.copy()

ts32011-01-02 0.4967

2011-01-05 -0.1383

2011-01-07 0.6477

2011-01-08 1.5230

2011-01-10 -0.2342

2011-01-12 -0.2341

dtype: float64ts4 = ts3.iloc[:3]

ts42011-01-02 0.4967

2011-01-05 -0.1383

2011-01-07 0.6477

dtype: float64ts4.iloc[:] = 2001

ts42011-01-02 2001.0000

2011-01-05 2001.0000

2011-01-07 2001.0000

dtype: float64ts32011-01-02 2001.0000

2011-01-05 2001.0000

2011-01-07 2001.0000

2011-01-08 1.5230

2011-01-10 -0.2342

2011-01-12 -0.2341

dtype: float64Series ts is unchanged because ts3 is an explicit copy of ts!

ts2011-01-02 0.4967

2011-01-05 -0.1383

2011-01-07 0.6477

2011-01-08 1.5230

2011-01-10 -0.2342

2011-01-12 -0.2341

dtype: float642.2 Time Series with Duplicate Indices

Most data in this course will be well-formed with one observation per datetime for series or one observation per individual per datetime for dataframes. However, you may later receive poorly-formed data with duplicate observations. The toy data in series dup_ts has three observations on February 2nd.

dates = pd.DatetimeIndex(['1/1/2000', '1/2/2000', '1/2/2000', '1/2/2000', '1/3/2000'])

dup_ts = pd.Series(data=np.arange(5), index=dates)

dup_ts2000-01-01 0

2000-01-02 1

2000-01-02 2

2000-01-02 3

2000-01-03 4

dtype: int32The .is_unique property tells us if an index is unique.

dup_ts.index.is_uniqueFalsedup_ts['1/3/2000'] # not duplicated4dup_ts['1/2/2000'] # duplicated2000-01-02 1

2000-01-02 2

2000-01-02 3

dtype: int32The solution to duplicate data depends on the context. For example, we may want the mean of all observations on a given date. The .groupby() method can help us here.

grouped = dup_ts.groupby(level=0)grouped.mean()2000-01-01 0.0000

2000-01-02 2.0000

2000-01-03 4.0000

dtype: float64grouped.last()2000-01-01 0

2000-01-02 3

2000-01-03 4

dtype: int32Or we may want the number of observations on each date.

grouped.count()2000-01-01 1

2000-01-02 3

2000-01-03 1

dtype: int643 Date Ranges, Frequencies, and Shifting

Generic time series in pandas are assumed to be irregular; that is, they have no fixed frequency. For many applications this is sufficient. However, it’s often desirable to work relative to a fixed frequency, such as daily, monthly, or every 15 minutes, even if that means introducing missing values into a time series. Fortunately pandas has a full suite of standard time series frequencies and tools for resampling, inferring frequencies, and generating fixed-frequency date ranges.

We will skip the sections on creating date ranges or different frequencies so we can focus on shifting data.

3.1 Shifting (Leading and Lagging) Data

Shifting is an important feature! Shifting is moving data backward (or forward) through time.

np.random.seed(42)

ts = pd.Series(

data=np.random.randn(4),

index=pd.date_range('1/1/2000', periods=4, freq='M')

)

ts2000-01-31 0.4967

2000-02-29 -0.1383

2000-03-31 0.6477

2000-04-30 1.5230

Freq: M, dtype: float64If we pass a positive integer \(N\) to the .shift() method:

- The date index remains the same

- Values are shifted down \(N\) observations

“Lag” might be a better name than “shift” since a postive 2 makes the value at any timestamp the value from 2 timestamps above (earlier, since most time-series data are chronological).

The .shift() method assumes \(N=1\) if we do not specify the periods argument.

ts.shift()2000-01-31 NaN

2000-02-29 0.4967

2000-03-31 -0.1383

2000-04-30 0.6477

Freq: M, dtype: float64ts.shift(1)2000-01-31 NaN

2000-02-29 0.4967

2000-03-31 -0.1383

2000-04-30 0.6477

Freq: M, dtype: float64ts.shift(2)2000-01-31 NaN

2000-02-29 NaN

2000-03-31 0.4967

2000-04-30 -0.1383

Freq: M, dtype: float64If we pass a negative integer \(N\) to the .shift() method, values are shifted up \(N\) observations.

ts.shift(-2)2000-01-31 0.6477

2000-02-29 1.5230

2000-03-31 NaN

2000-04-30 NaN

Freq: M, dtype: float64We will almost never shift with negative values (i.e., we will almost never bring forward values from the future) to prevent a look-ahead bias. We do not want to assume that financial market participants have access to future data. Our most common shift will be to compute the percent change from one period to the next. We can calculate the percent change two ways.

ts.pct_change()2000-01-31 NaN

2000-02-29 -1.2784

2000-03-31 -5.6844

2000-04-30 1.3515

Freq: M, dtype: float64(ts - ts.shift()) / ts.shift()2000-01-31 NaN

2000-02-29 -1.2784

2000-03-31 -5.6844

2000-04-30 1.3515

Freq: M, dtype: float64We can use np.allclose() to test that the two return calculations above are the same.

np.allclose(

a=ts.pct_change(),

b=(ts - ts.shift()) / ts.shift(),

equal_nan=True

)TrueTwo observations on the percent change calculations above:

- The first percent change is

NaN(not a number of missing) because there is no previous value to change from - The default

periodsargument for.shift()and.pct_change()is 1

The naive shift examples above shift by a number of observations, without considering timestamps or their frequencies. As a result, timestamps are unchanged and values shift down (positive periods argument) or up (negative periods argument). However, we can also pass the freq argument to respect the timestamps. With the freq argument, timestamps shift by a multiple (specified by the periods argument) of datetime intervals (specified by the freq argument). Note that the examples below generate new datetime indexes.

ts2000-01-31 0.4967

2000-02-29 -0.1383

2000-03-31 0.6477

2000-04-30 1.5230

Freq: M, dtype: float64ts.shift(2, freq='M')2000-03-31 0.4967

2000-04-30 -0.1383

2000-05-31 0.6477

2000-06-30 1.5230

Freq: M, dtype: float64ts.shift(3, freq='D')2000-02-03 0.4967

2000-03-03 -0.1383

2000-04-03 0.6477

2000-05-03 1.5230

dtype: float64M is already months, so T is minutes.

ts.shift(1, freq='90T')2000-01-31 01:30:00 0.4967

2000-02-29 01:30:00 -0.1383

2000-03-31 01:30:00 0.6477

2000-04-30 01:30:00 1.5230

dtype: float643.2 Shifting dates with offsets

We can also shift timestamps to the beginning or end of a period or interval.

from pandas.tseries.offsets import Day, MonthEnd

now = datetime(2011, 11, 17)

nowdatetime.datetime(2011, 11, 17, 0, 0)now + 3 * Day()Timestamp('2011-11-20 00:00:00')Below, MonthEnd(0) moves to the end of the month, but never leaves the month.

now + MonthEnd(0)Timestamp('2011-11-30 00:00:00')Next, MonthEnd(1) moves to the end of the month, unless already at the end, then moves to the next end of the month.

now + MonthEnd(1)Timestamp('2011-11-30 00:00:00')now + MonthEnd(1) + MonthEnd(1)Timestamp('2011-12-31 00:00:00')So, MonthEnd(2) uses 1 step to move to the end of the current month, then 1 step to move to the end of the next month.

now + MonthEnd(2)Timestamp('2011-12-31 00:00:00')Date offsets can help us align data for presentation or merging. But, be careful! The default argument is 1, but we typically want 0.

Here, MonthEnd(0) moves to the end of the current month, never leaving it.

datetime(2021, 10, 30) + MonthEnd(0)Timestamp('2021-10-31 00:00:00')datetime(2021, 10, 31) + MonthEnd(0)Timestamp('2021-10-31 00:00:00')Here, MonthEnd(1) moves to the end of the current month, leaving it only if already at the end of the month.

datetime(2021, 10, 30) + MonthEnd(1)Timestamp('2021-10-31 00:00:00')datetime(2021, 10, 31) + MonthEnd(1)Timestamp('2021-11-30 00:00:00')Always check your output!

4 Resampling and Frequency Conversion

Resampling is an important feature!

Resampling refers to the process of converting a time series from one frequency to another. Aggregating higher frequency data to lower frequency is called downsampling, while converting lower frequency to higher frequency is called upsampling. Not all resampling falls into either of these categories; for example, converting W-WED (weekly on Wednesday) to W-FRI is neither upsampling nor downsampling.

We can resample both series and data frames. The .resample() method syntax is similar to the .groupby() method syntax. This similarity is because .resample() is syntactic sugar for .groupby().

4.1 Downsampling

Aggregating data to a regular, lower frequency is a pretty normal time series task. The data you’re aggregating doesn’t need to be fixed frequently; the desired frequency defines bin edges that are used to slice the time series into pieces to aggregate. For example, to convert to monthly, ‘M’ or ‘BM’, you need to chop up the data into one-month intervals. Each interval is said to be half-open; a data point can only belong to one interval, and the union of the intervals must make up the whole time frame. There are a couple things to think about when using resample to downsample data:

- Which side of each interval is closed

- How to label each aggregated bin, either with the start of the interval or the end

rng = pd.date_range(start='2000-01-01', periods=12, freq='T')

ts = pd.Series(np.arange(12), index=rng)

ts2000-01-01 00:00:00 0

2000-01-01 00:01:00 1

2000-01-01 00:02:00 2

2000-01-01 00:03:00 3

2000-01-01 00:04:00 4

2000-01-01 00:05:00 5

2000-01-01 00:06:00 6

2000-01-01 00:07:00 7

2000-01-01 00:08:00 8

2000-01-01 00:09:00 9

2000-01-01 00:10:00 10

2000-01-01 00:11:00 11

Freq: T, dtype: int32We can aggregate the one-minute frequency data above to a five-minute frequency. Resampling requires and aggregation method, and here McKinney chooses the .sum() method.

ts.resample('5min').sum()2000-01-01 00:00:00 10

2000-01-01 00:05:00 35

2000-01-01 00:10:00 21

Freq: 5T, dtype: int32Two observations about the previous resampling example:

- For minute-frequency resampling, the default is that the new data are labeled by the left edge of the resampling interval

- For minute-frequency resampling, the default is that the left edge is closed (included) and the right edge is open (excluded)

As a result, the first value of 10 at midnight is the sum of values at midnight and to the right of midnight, excluding the value at 00:05 (i.e., \(10 = 0+1+2+3+4\) at 00:00 and \(35 = 5+6+7+8+9\) at 00:05). We can use the closed and label arguments to change this behavior.

In finance, we generally prefer closed='right' and label='right' to avoid a lookahead bias.

ts.resample('5min', closed='right', label='right').sum() 2000-01-01 00:00:00 0

2000-01-01 00:05:00 15

2000-01-01 00:10:00 40

2000-01-01 00:15:00 11

Freq: 5T, dtype: int32Mixed combinations of closed and label are possible but confusing.

ts.resample('5min', closed='right', label='left').sum() 1999-12-31 23:55:00 0

2000-01-01 00:00:00 15

2000-01-01 00:05:00 40

2000-01-01 00:10:00 11

Freq: 5T, dtype: int32These defaults for minute-frequency data may seem odd, but any choice is arbitrary. I suggest you do the following when you use the .resample() method:

- Read the docstring

- Check your output

pandas and its .resample() method are mature and widely used, so the defaults are typically reasonable.

4.2 Upsampling and Interpolation

To downsample (i.e., resample from higher frequency to lower frequency), we aggregate data with an aggregation method (e.g., .mean(), .sum(), .first(), or .last()). To upsample (i.e., resample from lower frequency to higher frequency), we do not aggregate data.

np.random.seed(42)

frame = pd.DataFrame(

data=np.random.randn(2, 4),

index=pd.date_range('1/1/2000', periods=2, freq='W-WED'),

columns=['Colorado', 'Texas', 'New York', 'Ohio']

)

frame| Colorado | Texas | New York | Ohio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01-05 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-12 | -0.2342 | -0.2341 | 1.5792 | 0.7674 |

We can use the .asfreq() method to convert to the new frequency and leave the new times as missing.

df_daily = frame.resample('D').asfreq()

df_daily| Colorado | Texas | New York | Ohio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01-05 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-06 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-07 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-08 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-09 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-10 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-11 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-12 | -0.2342 | -0.2341 | 1.5792 | 0.7674 |

We can use the .ffill() method to forward fill values to replace missing values.

frame.resample('D').ffill()| Colorado | Texas | New York | Ohio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01-05 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-06 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-07 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-08 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-09 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-10 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-11 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-12 | -0.2342 | -0.2341 | 1.5792 | 0.7674 |

frame.resample('D').ffill(limit=2)| Colorado | Texas | New York | Ohio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01-05 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-06 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-07 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-08 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-09 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-10 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-11 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2000-01-12 | -0.2342 | -0.2341 | 1.5792 | 0.7674 |

frame.resample('W-THU').ffill()| Colorado | Texas | New York | Ohio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01-06 | 0.4967 | -0.1383 | 0.6477 | 1.5230 |

| 2000-01-13 | -0.2342 | -0.2341 | 1.5792 | 0.7674 |

5 Moving Window Functions

Moving window (or rolling window) functions are one of the neatest features of pandas, and we will frequently use moving window functions. We will use data similar, but not identical, to the book data.

df = (

yf.download(tickers=['AAPL', 'MSFT', 'SPY'])

.rename_axis(columns=['Variable', 'Ticker'])

)

df.head()[*********************100%%**********************] 3 of 3 completed| Variable | Adj Close | Close | High | Low | Open | Volume | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticker | AAPL | MSFT | SPY | AAPL | MSFT | SPY | AAPL | MSFT | SPY | AAPL | MSFT | SPY | AAPL | MSFT | SPY | AAPL | MSFT | SPY |

| Date | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1980-12-12 | 0.0992 | NaN | NaN | 0.1283 | NaN | NaN | 0.1289 | NaN | NaN | 0.1283 | NaN | NaN | 0.1283 | NaN | NaN | 469033600.0000 | NaN | NaN |

| 1980-12-15 | 0.0940 | NaN | NaN | 0.1217 | NaN | NaN | 0.1222 | NaN | NaN | 0.1217 | NaN | NaN | 0.1222 | NaN | NaN | 175884800.0000 | NaN | NaN |

| 1980-12-16 | 0.0871 | NaN | NaN | 0.1127 | NaN | NaN | 0.1133 | NaN | NaN | 0.1127 | NaN | NaN | 0.1133 | NaN | NaN | 105728000.0000 | NaN | NaN |

| 1980-12-17 | 0.0893 | NaN | NaN | 0.1155 | NaN | NaN | 0.1161 | NaN | NaN | 0.1155 | NaN | NaN | 0.1155 | NaN | NaN | 86441600.0000 | NaN | NaN |

| 1980-12-18 | 0.0919 | NaN | NaN | 0.1189 | NaN | NaN | 0.1194 | NaN | NaN | 0.1189 | NaN | NaN | 0.1189 | NaN | NaN | 73449600.0000 | NaN | NaN |

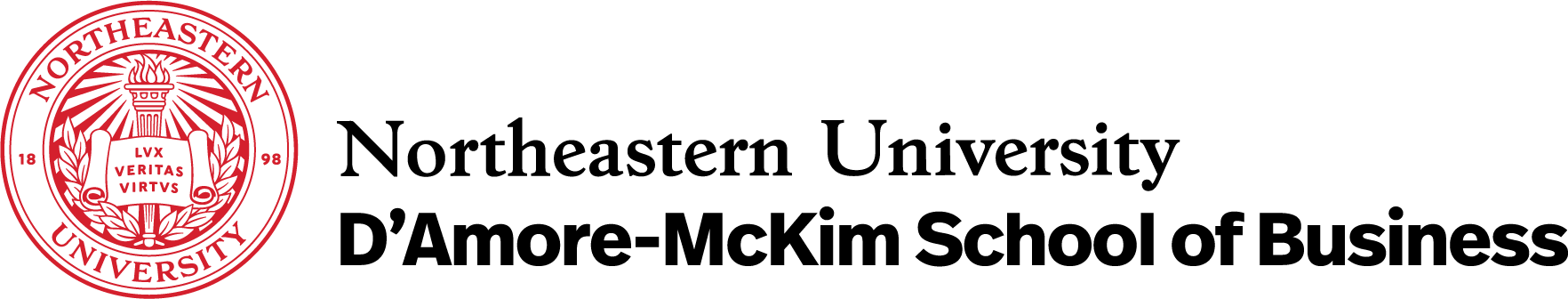

The .rolling() method is similar to the .groupby() and .resample() methods. The .rolling() method accepts a window-width and requires an aggregation method. The next example calculates and plots the 252-trading day moving average of AAPL’s price alongside the daily price.

aapl = df.loc['2012':, ('Adj Close', 'AAPL')]

aapl.plot(label='Observed')

aapl.rolling(252).mean().plot(label='252 Trading Day Mean') # min_periods defaults to 252

aapl.rolling('365D').mean().plot(label='365 Calendar Day Mean') # min_periods defaults to 1

aapl.resample('A').mean().plot(style='.', label='Calendar Year Mean')

plt.legend()

plt.ylabel('AAPL Adjusted Close ($)')

plt.title('Comparison of Rolling and Resampling Means')

plt.show()

Two observations:

- If we pass the window-width as an integer, the window-width is based on the number of observations and ignores time stamps

- If we pass the window-width as an integer, the

.rolling()method requires that number of observations for all windows (i.e., note that the moving average starts 251 trading days after the first daily price

We can use the min_periods argument to allow incomplete windows. For integer window widths, min_periods defaults to the given integer window width. For string date offsets, min_periods defaults to 1.

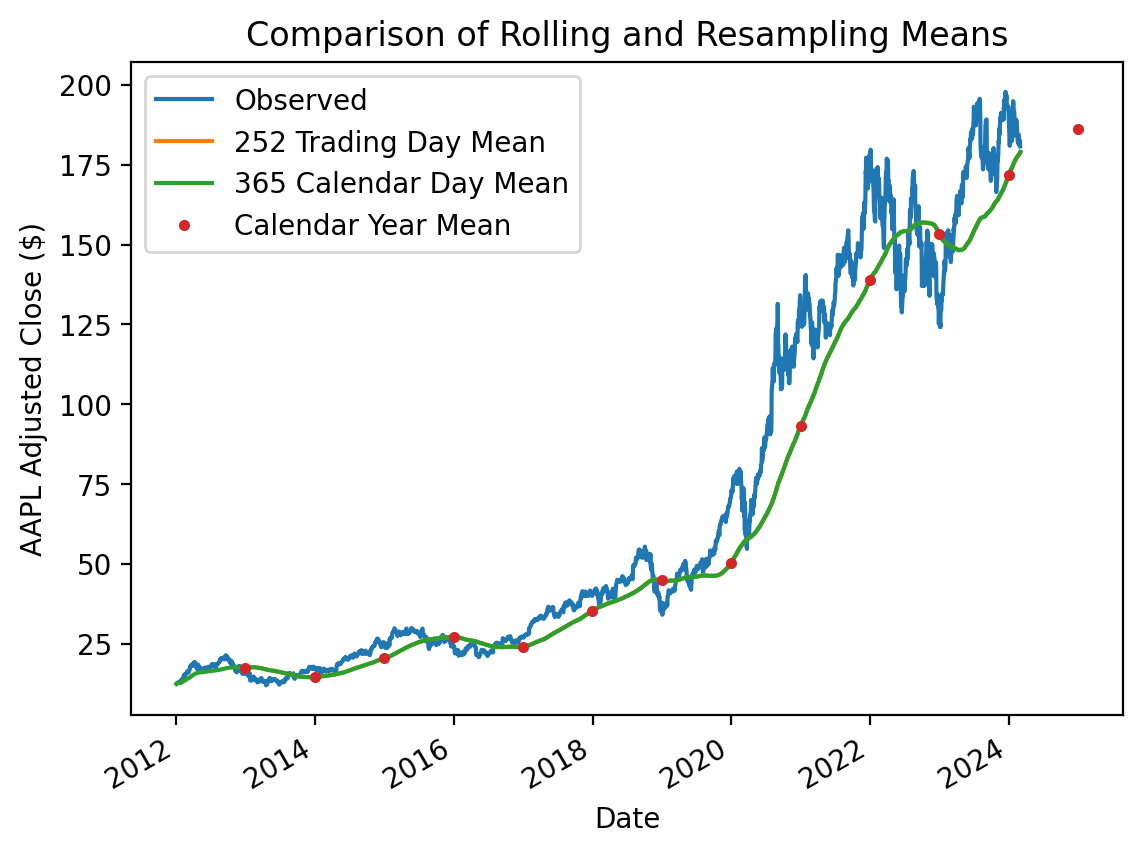

5.1 Binary Moving Window Functions

Binary moving window functions accept two inputs. The most common example is the rolling correlation between two returns series.

returns = df['Adj Close'].iloc[:-1].pct_change()

returns| Ticker | AAPL | MSFT | SPY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | |||

| 1980-12-12 | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 1980-12-15 | -0.0522 | NaN | NaN |

| 1980-12-16 | -0.0734 | NaN | NaN |

| 1980-12-17 | 0.0248 | NaN | NaN |

| 1980-12-18 | 0.0290 | NaN | NaN |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 2024-02-23 | -0.0100 | -0.0032 | 0.0007 |

| 2024-02-26 | -0.0075 | -0.0068 | -0.0037 |

| 2024-02-27 | 0.0081 | -0.0001 | 0.0019 |

| 2024-02-28 | -0.0066 | 0.0006 | -0.0013 |

| 2024-02-29 | -0.0037 | 0.0145 | 0.0036 |

10894 rows × 3 columns

(

returns['AAPL']

.rolling(126, min_periods=100)

.corr(returns['SPY'])

.plot()

)

plt.ylabel('Correlation between AAPL and SPY')

plt.title('Rolling Correlation between AAPL and SPY\n (126-Day Window w/ 100-Day Minimum)')

plt.show()

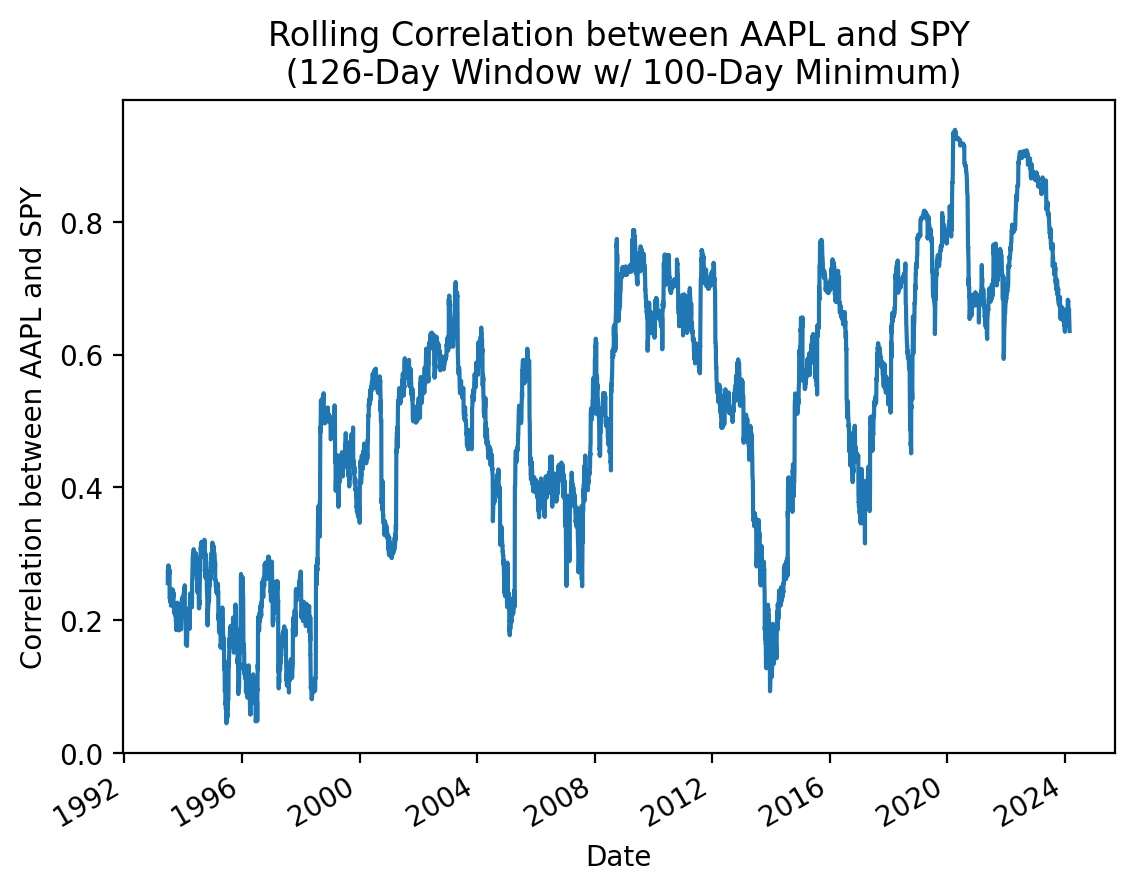

(

returns[['AAPL', 'MSFT']]

.rolling(126, min_periods=100)

.corr(returns['SPY'])

.plot()

)

plt.ylabel('Correlation with SPY')

plt.title('Rolling Correlation with SPY\n (126-Day Window w/ 100-Day Minimum)')

plt.show()

5.2 User-Defined Moving Window Functions

Finally, we can define our own moving window functions and use the .apply() method to apply them However, note that .apply() will be much slower than the the optimized moving window functions (e.g., .mean(), .std(), etc.).

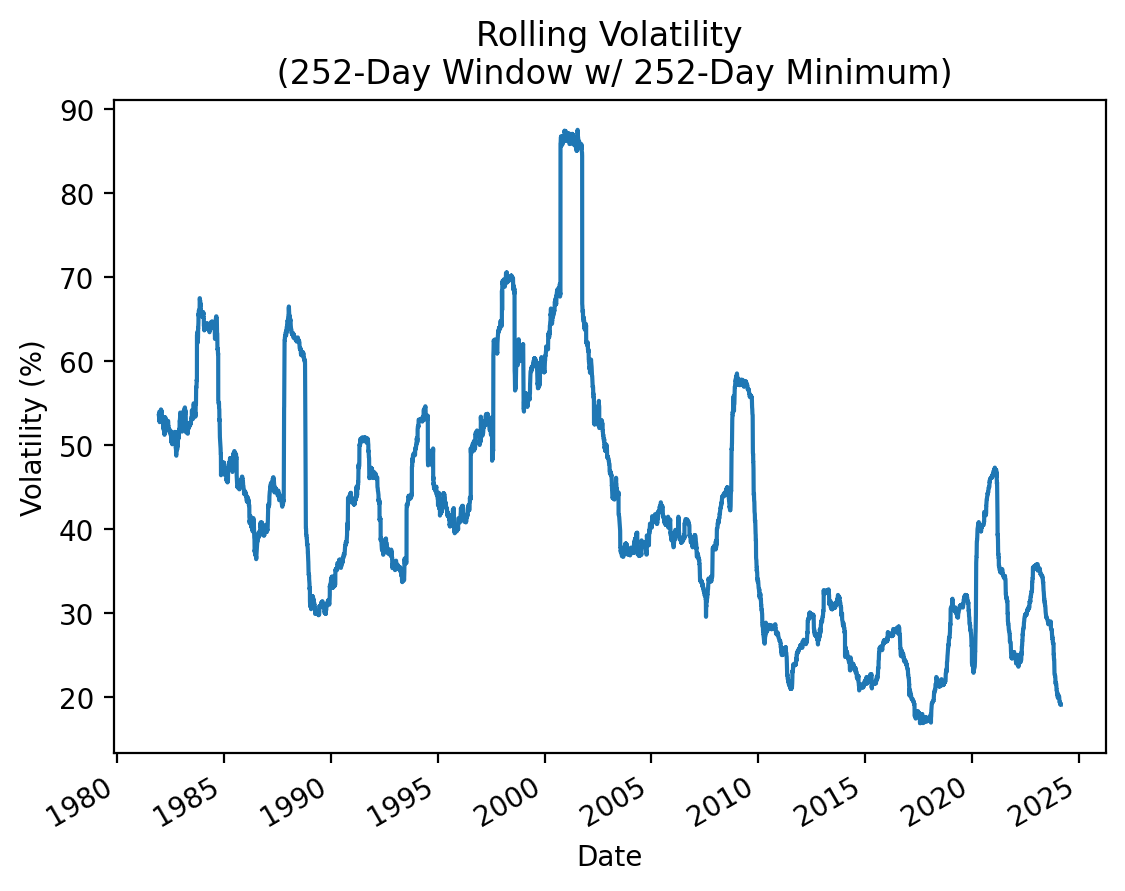

McKinney provides an abstract example here, but we will discuss a simpler example that calculates rolling volatility. Also, calculating rolling volatility with the .apply() method provides us a chance to benchmark it against the optimized version.

(

returns['AAPL']

.rolling(252)

.apply(np.std)

.mul(np.sqrt(252) * 100)

.plot()

)

plt.ylabel('Volatility (%)')

plt.title('Rolling Volatility\n (252-Day Window w/ 252-Day Minimum)')

plt.show()

Do not be afraid to use .apply(), but realize that .apply() is typically 1000-times slower than the pre-built method.

%timeit returns['AAPL'].rolling(252).apply(np.std)902 ms ± 148 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)%timeit returns['AAPL'].rolling(252).std()244 µs ± 11.8 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1,000 loops each)